To Stay or To Go?

The Battle of Monuments Discussed in Smashing Statues

By: Avery Calvert, The University of North Alabama

"But monuments aren't history lessons—they’re pledges of allegiance."[1] This thought-provoking quote from Erin Thompson’s book Smashing Statues: The Rise and Fall of America’s Public Monuments encourages readers to take on a new perspective when thinking about public monuments in the United States. In fact, her entire book is based on just that—encouraging the reader to realize that many public monuments were erected to stifle progress.

Erin Thompson is an American lawyer and art historian who earned both her J.D. and Ph.D. from Columbia University. Currently, Thompson is America’s only professor specializing in art crime, which covers a variety of subjects from black market antiquities to art created by detainees at Guantanamo Bay.[2] This unique historical perspective allows Thompson’s readers to evaluate art from both legal and historical standpoints.

Humans express themselves through art; none of these are as controversial as statues. Since the ancient Greeks, statues have been used as a symbol of adoration. Statues say something about a society’s views. If statues reflect a society’s views, then why are monuments that were made centuries ago still erect? Throughout her book, Thompson provides several case studies that evaluate why controversial statues were created, are left up, and what can be done about them. I will evaluate one of these case studies: Stone Mountain.

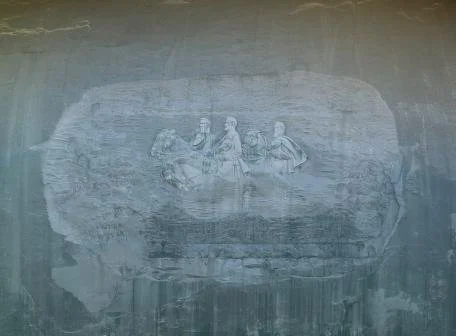

Carol M. Highsmith, 1980, photography, Stone Mountain, Georgia.

Stone Mountain located in Georgia is the largest Confederate monument in the United States. Now if you are like me and vacationed there when you were younger, you may not realize the tumultuous history that comes with this mountain. The project was commissioned by the Atlanta chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Caroline Helen Jemison Plane, founder of the chapter, organized the carving of Stone Mountain under a special committee formed within the United Daughters of the Confederacy: the Stone Mountain Memorial Association. In June 1915, the association invited Gutzon Borglum to be the sculptor and the project began. After his appointment Borglum set to work on Stone Mountain. He hired mainly African American quarry workers. These men were not allowed to showcase their creativity, they were only allowed to carry supplies and complete prep work.[3] Mere days after the appointment of Borglum, the Ku Klux Klan used this mountain to revive their organization. They stood upon Stone Mountain and burned a wooden cross, an activity they consistently did until the 1990s.[4] It was here that the Klansmen took their oath and revived their organization.[5]

In 1923, the KKK helped raise funds for the carving of Stone Mountain through the selling of commemorative half-dollar coins, which ultimately failed due to a lack of sales.[6] The state of Georgia then purchased the monument in 1958 and completed the carvings in 1972.[7] The carvings on Stone Mountain were being worked on and completed at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, and it is not a coincidence that the then newly elected governor of Georgia, Marvin Griffin, changed the Georgia state flag to the Confederate flag before purchasing Stone Mountain.[8] The completion of the carvings and new state flag. The Stone Mountain project took fifty-seven years to complete, and while the project stopped numerous times, it always seemed to be championed by a white supremacist group. Now, Stone Mountain has been turned into a park with various attractions. Families can enjoy the fun while Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson look on from the mountain above. Revealing that ignoring issues of white supremacy and racism continue to be societal norms in the South.

Throughout this case study, we discover several motives for Stone Mountain’s creation. One is the honoring of Confederate soldiers who fought in the war. The other is the Klan’s white supremacy agenda. But the question remains: what does Stone Mountain really stand for? Considering its size and the money that it would take to blast the relief off the mountain, it is just not feasible to clear the relief now. What is feasible is the education that can occur at a site like this. As of now, the official Stone Mountain Park website does not mention the Klan’s involvement in funding the monument nor does it mention that the mountain was purchased as a reaction to the Civil Rights Movement.[9] By acknowledging harsh truths such as these, visitors can understand the broader picture of Stone Mountain’s history and learn to make the best of difficult history.

Overall, Smashing Statues illustrates the complexity of dealing with difficult histories. Throughout our entire nation, there are many statues and memorials that people do not understand the complexities of their creation. By illuminating not only the history that the statue is preserving but also the history of the statue itself, people can learn the intentions of the statues enabling them to better evaluate if they should stay or go.

Notes

[1] Erin L. Thompson, Smashing Statues: The Rise and Fall of America's Public Monuments (New York City: W. W. Norton, 2022), xviii.

[2] “Erin Thompson,” John Jay College of Criminal Justice, February 21st, 2024, https://www.jjay.cuny.edu/faculty/erin-thompson.

[3] Erin L. Thompson, Smashing Statues: The Rise and Fall of America's Public Monuments (New York City: W. W. Norton, 2022), 79.

[4] Erin L. Thompson, Smashing Statues: The Rise and Fall of America's Public Monuments (New York City: W. W. Norton, 2022), 90.

[5] Erin L. Thompson, Smashing Statues: The Rise and Fall of America's Public Monuments (New York City: W. W. Norton, 2022), 75-77.

[6] Erin L. Thompson, Smashing Statues: The Rise and Fall of America's Public Monuments (New York City: W. W. Norton, 2022), 84.

[7] “Memorial Carving,” Stone Mountain Park, February 21st, 2024, https://stonemountainpark.com/activity/history-nature/memorial-carving/.

[8] Erin L. Thompson, Smashing Statues: The Rise and Fall of America's Public Monuments (New York City: W. W. Norton, 2022), 91.

[9] “Memorial Carving,” Stone Mountain Park, February 21st, 2024, https://stonemountainpark.com/activity/history-nature/memorial-carving/.